The loss of a grandson. The birth of a grandmother’s mission.

NEW SAN ACACIO – Cynthia Trevino Ozuna is a woman of compassion and abiding faith. A woman suddenly widowed in 2014, suddenly a single mother to a blended family of thirteen children with three still in school. A woman who calls everyone “honey” and means it, whether friend or stranger, young or old.

Ozuna drives a school bus for special needs students, picking them up in Alamosa, taking them to Centauri and then bringing them home.

“I love those kids so much,” she says.

To Ozuna, “kids” includes everyone from toddlers to people in their twenties. In San Luis and nearby New San Acacio where she lives, she knows them all, has known them “since they were in kindergarten.”

She knows, too, the struggles they’ve both endured and caused. She “loves them all” without judgment but with no small measure of pain for the pain she knows many suffer.

“I’ve seen so many suicides, honey. So many deaths from drugs and alcohol and murder. It breaks my heart. Someone has to do something.”

Ozuna has been saying that for a long time. But it was an enormous loss in her life that inspired her to be that somebody who helps.

Mario Trevino, Ozuna’s grandson, was one month shy of his twentieth birthday when he died.

“He was very bright. When he was two years old, he could do a hundred-piece puzzle faster than I could. He loved Spiderman. We’d go to the mall in Colorado Springs. He loved sliding on that smooth floor, pretending he was Spiderman, throwing out the spider web and saving people.

“My hijito…” She pauses when the tears come. “He was a loving kid with such a big heart. He’d do tooth and nail for the people he loved.”

Life wasn’t always easy for Mario. As a little boy living in south Denver, he sometimes returned to the valley where his family visited Ozuna, his step grandfather and the multitude of relatives and friends.

It was a good place for him to be, surrounded by love and acceptance.

When Mario was five years old, his father died. The family was devastated but none more so than his mother, Sonja, whose sorrow was so deep that the five-year-old boy hid his father’s picture to keep his mother from being sad.

When he first started school, Mario excelled, “zipping through his work.” But he started having difficulty concentrating and “sitting still”. Sonja took him to a doctor who diagnosed him with ADHD and put him on Ritalin.

“My hijito wasn’t himself on that medication. He just played his games and was very unsocial. That wasn’t like Mario at all.” Even as bright as he was, even on medication, Mario continued to struggle.

The doctor tried different medications, but they only added more complications. Sonja ultimately stopped and tried more natural treatments.

“Listening to music helped. Music was his tranquility.”

When Mario was twelve years old, life dealt another blow when his step grandfather passed away.

His loss threw the family into a tailspin, especially Ozuna who suddenly found herself the only wage earner and three young sons to raise.

“I got the boys into counselling. It lasted a little while, but they didn’t want to go back. I worried so about Mario. He’d already lost his dad and then he lost my husband. But Mario was in Denver. I was here. There was only so much I could do.”

When he was fifteen, Mario began smoking marijuana. “His friends in Denver were different, and I think some of it was peer pressure. But marijuana actually relaxed him. It calmed him down and helped him think.”

But the trouble at school escalated. After being expelled at the age of sixteen, Mario came to live with Ozuna.

“His friends here were so happy to see him. But there isn’t much for a teenager to do here. One day, I found a bottle of liquor in his room. That worried me a lot. I talked to him for a long time. I told him he shouldn’t drink. It was bad for him. I asked him if he did other drugs. He said he tried psychedelics once. But he told me, ‘That’s no good, Grandma. I didn’t like it.’ We talked and he listened. Mario always listened.”

At the end of the year, Mario returned to Denver where he eventually turned a corner. He started taking GED classes online. He worked odd jobs for neighbors, always within a few blocks from his home, always giving part of his pay to his mother.

On March 24, Mario called Ozuna early in the morning. “He said, ‘Grandma, I just want you to know I’m doing good.’ He told me he loved me and he loved everybody here and wanted me not to worry because he was doing good.”

Tears come, but she keeps speaking. “Just a few hours later, they told me he was gone. They’d tried calling him and when he didn’t answer, my ex-husband went looking. He’d just driven up to the house of one of Mario’s friends when they were bringing out his body. Mario had gone over there during lunch to smoke a little marijuana. It was laced with fentanyl. The fentanyl killed him.”

It was not the first time fentanyl had brought death to Ozuna’s family. A few months earlier, her niece had stopped by her nephew’s house where she found her brother, his wife, his wife’s brother and two others dead from an unintentional overdose of the drug.

As reported by the Denver Post, investigators believe the group thought they were ingesting cocaine, unaware it had been laced with the synthetic opiate. “They died instantly. They didn’t stand a chance,” an investigator told the Post.

“It’s everywhere, honey.” There’s palpable anguish in her voice. “People are dying. I had to do something.”

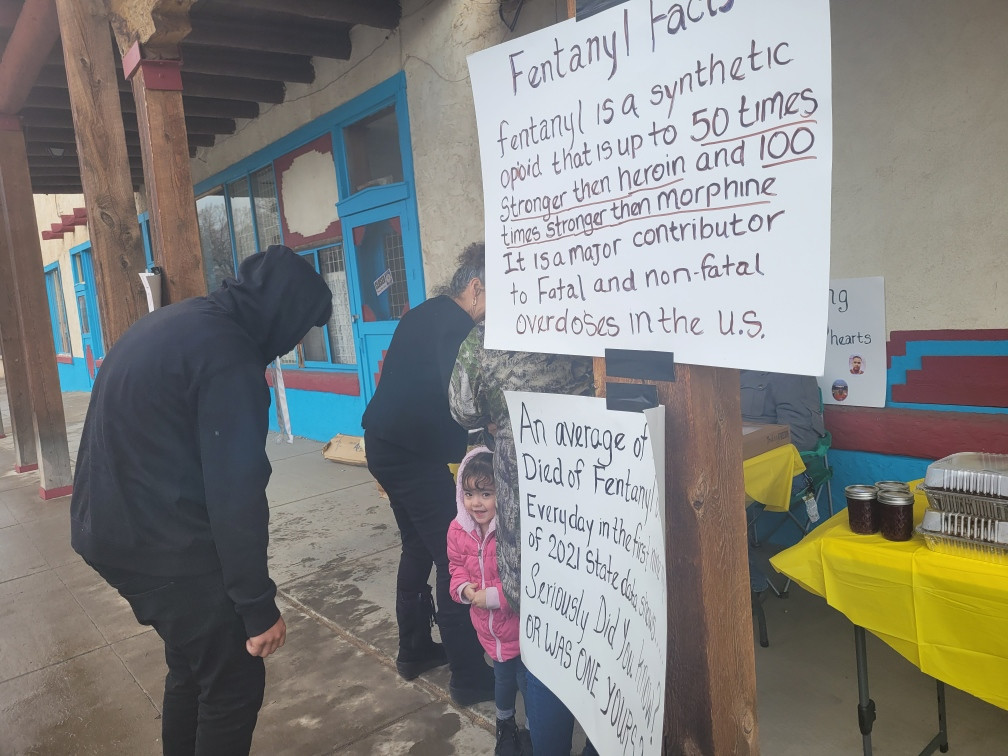

That “something” started when Ozuna held a bake sale outside the market in San Luis to raise money for Mario’s funeral. On the wall behind the table, she hung signs she’d made, warning about the dangers of fentanyl. There was an outpouring of support from the community, with $900 raised in just a few hours from selling cookies and cakes.

But a conversation with a woman struck the most profound chord.

“She told me, ‘Don’t feel bad for saying how Mario died. We’ve all lost somebody to drugs but we keep it hushed because we don’t want others to know.’ She told me it was good for mothers to talk to each other.”

Since then, Ozuna has talked to mothers in the valley and in Denver. She has stood outside City Market with the signs she made. She has gone to clinics and hospitals across the valley asking what else she can do. They have given her papers to pass out that are nothing but statistics.

“These kids are dealing with so much. It’s killing them, honey. There’s so much instability. Moms and dads gone from the house. Nothing to do but drink and do drugs. We need young men to mentor these kids. There’s so much desperation. There has to be hope. At least a sliver of hope. My faith in God keeps me strong. I think this is what God wants me to do since my Mario died. If it helps one person, saves one person, at least that’s something. That’s something.”